Individual Tree and Woodlot Inventory, and the Tree Inspection Cycle

Bardekjian, A. & Puric-Mladenovic, D. (2025). Individual Tree and Woodlot Inventory, and the Tree Inspection Cycle. In Growing Green Cities: A Practical Guide to Urban Forestry in Canada. Tree Canada. Retrieved from Tree Canada: https://treecanada.ca/urban-forestry-guide/individual-tree-and-woodlot-inventory-and-the-tree-inspection-cycle/

Highlights

Importance of tree inventories

Tree inventories are essential for urban forestry and provide valuable data for foresters, planners, policymakers, and homeowners.

Inventory details

Tree species, health, size, and location.

Data collection methods

Inventories and inspections can be done at various spatial scales, either manually or remotely.

Citizen science and community involvement

Volunteer-based inventories can be a cost-effective and socially beneficial way to start or update a city’s tree inventory.

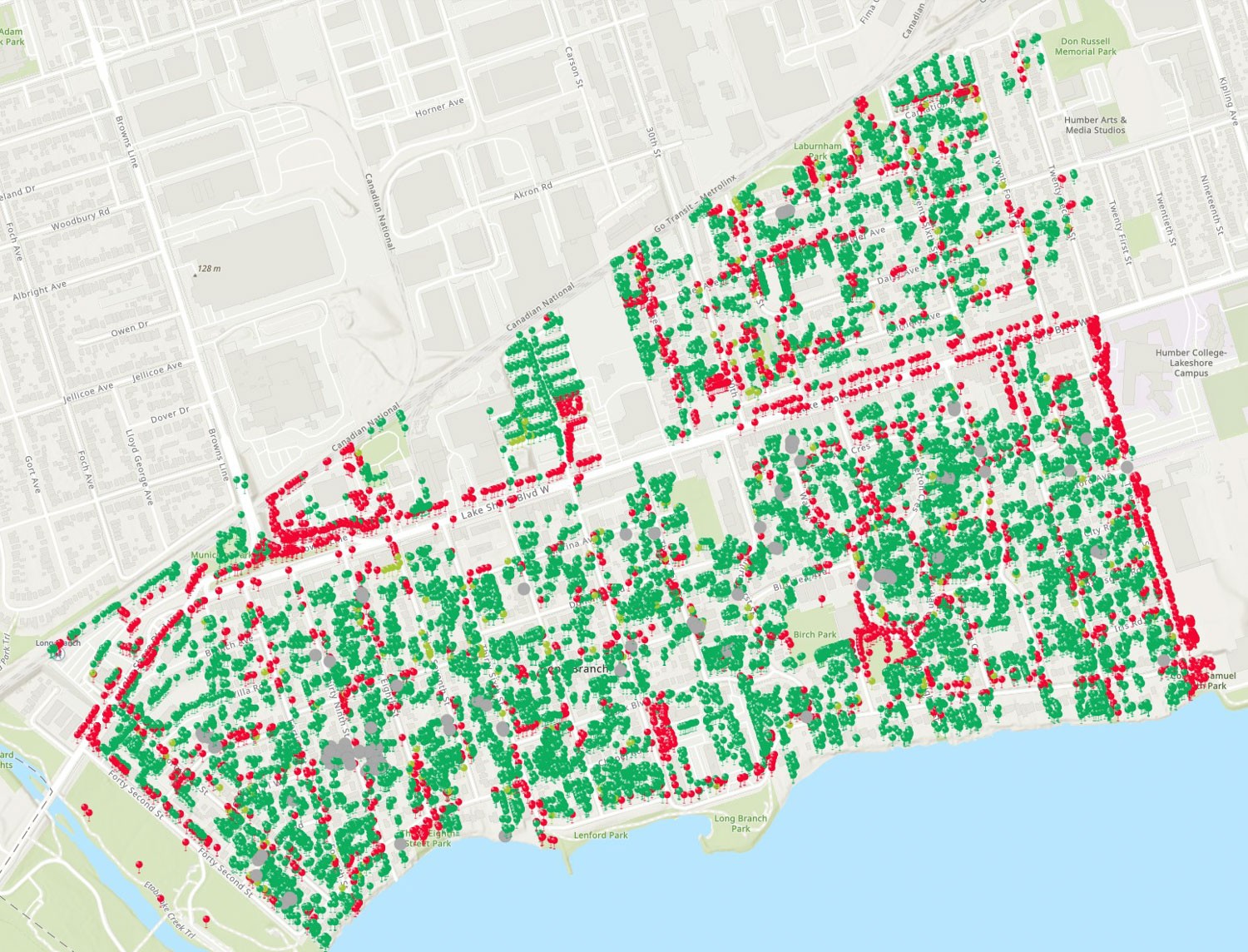

The structure, distribution, and composition of an urban tree canopy greatly impact the benefits and services provided by urban green spaces in Canadian cities (Przewoźna et al., 2022). The foundation of an effective urban forest management program and the base information supporting ecological service estimates comes from a detailed tree inventory. A tree inventory is a necessary urban forest management tool that provides information about trees, such as tree species, health, size, and location. There are diverse ways in which city authorities, professionals, and researchers can use tree inventory data. Inventory data can be used to identify and analyze tree species diversity and distribution, percentage of canopy cover, tree size/class distribution, functional group distribution, tree health and growth trends, and more (Nielsen, Delshammer & Ostberg, 2014). Tree inventory data can also be used to support various efforts such as strategic forest management plans, cost-benefit assessments of urban climate/pollution mitigation, creation of invasive species management plans, risk assessment, examination of social dimensions of urban forests, and much more (City of Toronto, 2013). Forest managers can also prioritize maintenance efforts and resources by knowing urban forest resources. As such, keeping an up-to-date inventory of urban trees, supplemented by routine tree inspection, is fundamental for effective urban forest management.

Sample-Based Inventory

There are several different methods and scopes of tree inventory that a city can employ. The quickest and most minimal scope of inventory is a sample-based inventory, which contains information on a small subset of trees from a larger population. A sample with sufficient data enables urban foresters to extrapolate tree data across the city to represent an entire urban forest. This type of inventory is considered a cost-effective way to achieve a statistically valid representation of an urban forest when the scope of inventory and analysis does not require data on each tree for specific management applications (Sabatini, 2021). Similarly, partial tree inventories focus on certain areas of concern, such as specific tree species, land use categories, or geographic areas. This type of inventory is taken when dealing with a pest outbreak and species-specific pests and diseases, as with the Emerald Ash Borer. A partial inventory is also useful when assessing storm damage and when performing risk assessments (EFUF, 2018).

Individual Tree Inventory

When a more comprehensive analysis of urban trees is required to support tree management and daily maintenance, tree surveys/inventories at the level of individual trees may be conducted. Survey methods include direct inspection and measurement of individual trees to gather a complete record of species, age, size, health, location, and other qualities (Nielsen, Delshammer & Ostber, 2014; Morales-Gallegos et al., 2023). While this approach can be labour-intensive and time-consuming, it supports urban forest management and operations with the most thorough and accurate tree data. Individual tree inventories may be considered the most beneficial inventory method in situations when analyzing tree species diversity and distribution, tree size/class distribution, and monetary evaluation of individual trees/species are required, such as for preparing tree planting prescriptions or creating a baseline inventory for further assessment (Urban Forest Analytics, 2024).

Tree Inspection

A tree inspection cycle, coupled with an updated tree inventory, is integral for proper tree maintenance and hazard management. Effective tree monitoring enables the evaluation of urban forest resources and the development of short and long-term plans and maintenance, which can provide substantial cost savings while also mitigating safety and tree hazard issues.

Urban tree inspection, pruning, and removal are necessary components of urban forestry in Canada [see chapter: Tree Maintenance]. Up-to-date inspection of urban street tree condition and health, as well as recording previous and scheduled work, are the basis of effective street tree maintenance and management (City of Toronto, 2013). Regular inspection cycles are also important health and safety tools, where storm or construction tree damage, canopy dieback, limb damage, pest and disease presence, routine tree care and tree health decline can be assessed and managed in a timely manner to prevent hazards and risks to citizens (International Society of Arboriculture, n.d.).

Tree health indicators at the individual tree level such as trunk damage, crown dieback, vandalism, pest/disease presence and root damage require on-the-ground inspection (Morales-Gallegos et al., 2023), while street- or stand-level health indicators such as crown density, stand age/size, vegetation indices, edaphic (soil-related) factors and climatic/environmental stressors can be inspected and observed using satellite imagery, sample inventories, proxy indicators and models (Haq et al., 2023).

Aerial Urban Forest Inventory

Conversely, when general tree data is required for large areas, many Canadian cities create tree inventories using aerial photography and GIS (Esri Canada & City of Guelph, n.d.). By employing satellite imagery and scanning tools, cities can conduct an inventory of tree cover types and general stand qualities without inspecting each individual tree [see chapter: GIS, Remote Sensing and Other Spatial Technologies]. This type of inventory can be beneficial when considering the health and benefits of urban canopy cover, when assessing large areas where field surveys may be too costly/time-intensive, and when information about individual trees is not necessary based on the scope of data application (Wood, Norton & Rowland, n.d.; Nielsen, Delshammer & Ostber, 2014).

Community Science and Participation

When conducting tree inventories, Canadian cities may employ citizens and non-profit organizations to participate in data collection. Recruiting volunteers to record general observations about tree health in their neighbourhoods, such as cavity decay, crown dieback, and trunk damage, is a valuable and cost-effective way to build and maintain tree health inventories without performing constant field surveys (Sabatini, 2021). In Canada, community-based stewardship programs such as Neighbourwoods™ (Kenney & Puric-Mladenovic, 1995) can help community groups and volunteers contribute to tree inventories, which help inform foresters and planners about the state of urban forests while also encouraging community involvement in urban forest stewardship. This program has explicitly been employed in several municipalities across Ontario and has potential for application across Canada and beyond. Additionally, Canadian urban tree inventory data can be added to national and international databases (e.g., CIF Open Urban Forests (2024), i-Tree (n.d.), Making Nature’s City ToolKit (n.d.), etc.), which support concerted management and planning efforts.

It is important to recognize that many community involvement and volunteer-based outreach programs only reach a very targeted audience. There is often a lack of emphasis on place-based landscape design and engagement, which should vary based on the needs of individual neighbourhoods, communities, and municipalities (Eisenman et al., 2024). A place-based approach to community engagement in urban forestry requires understanding the issues, relationships, and needs of community members in any given place and specifically coordinating planning and resources to improve the quality of life for that community (Improvement Service UK, 2016). When place-based needs and goals are not well understood, the benefits of community involvement in urban forestry can be inequitably distributed (Kudryavtsev, Stedman & Krasny, 2012).

For a successful and equitable place-based outreach program, it is necessary to allocate funds properly, meaningfully consult with target volunteers, co-develop participation opportunities with community members, and select performance outcomes based on place-based needs and goals (Eisenman et al., 2024). People from all communities should be equally able to engage in urban forestry, so public participation programs should reflect their specific needs and goals [see chapter: Equity Considerations in Urban Forestry].

Natural Area/Woodlot Inventory

Contents

- Urban woodlots and natural areas

- Management goals: Determine the type of inventory that should be used.

- Inventory methods: Selecting inventory methods, scale, and sampling plan.

- Monitoring woodlots and natural areas: Ongoing process of tracking changes in forest communities over time and space.

Effective woodlot, natural parks, and area management rely on accurate knowledge of plant species composition, community structure, and how healthy its components are. Woodlot inventories differ from street tree inventories both in their spatial extent and in that a woodlot will have trees grown from naturally occurring seed, understory plants, wildlife, and other components not controlled by humans. Woodlot inventories can range from a basic timber cruise to a detailed inventory including soil, vegetation community, and wildlife inventory. The management goals for the woodlot generally determine the type of inventory chosen for a project. However, it is important to keep in mind that an inventory may bring to light new information (such as the presence of a species at risk or invasive plants) that might change management goals (Ma et al., 2021).

The first step in understanding what is in a woodlot is a survey of available aerial images and maps. Depending on when and why they were developed, existing maps may already delineate the different stand types, roads, and water bodies in a woodlot. Aerial imagery can be used to create these maps and to judge the accuracy of outdated or broad-scale maps when newer information is not available (Gougeon, 2014). Forest resource inventory maps are variably available across Canada and may be found through provincial open spatial data hubs [see chapter: National and Provincial Datasets]. LiDAR mapping may also be an option for stand delineation (Wang et al., 2004).

After getting a basic idea of what stands and other features are present in a woodlot, a sampling plan can be developed to build a basic inventory. The simplest form of woodlot inventory sampling is a timber cruise. In this form of inventory, sample locations (plots of variable size) are selected where surveyors record tree species, diameter, and growth form, which are then used to estimate the number of each tree species and the amount of basal area and merchantable timber per hectare. There are many guides to timber cruising provided by provincial governments and woodlot associations. However, this kind of inventory does not provide sufficient information on forest structure, composition, plant diversity, non-tree plant species, soil condition, forest community, and other aspects of woodlots, which determine their ecological integrity, combined health, and classification. A more detailed inventory, often based on fixed area plots and which collects data on species besides trees as well as site characteristics, can better support tailored management for multiple purposes such as monitoring, habitat and species-at-risk protection, regeneration success, recreation, or carbon stock (Day and Puric-Mladenovic, 2012). One such inventory and monitoring program is the Vegetation Sampling Protocol (VSP) (Puric-Mladenovic, 2016), which can be adjusted to different spatial scales depending on landscape and management needs (Puric-Mladenovic & Baird, 2017). VSP is a sampling protocol that collects multipurpose, detailed information on trees and their size, but also a full species list, dead wood, and invasive species abundance (Sherman, 2015). VSP, as a strategic inventory, gathers information that is multi-functional and standardized (data collection and web-based portal for data entry), and gives a precise record of spatial extent and location, enabling field data to be transferred into diverse spatial formats and vegetation mapping products. It is also used for monitoring as it enables resampling and tracking changes in forest ecosystems over time and space. Detailed protocols such as this can be great resources when creating detailed inventories and flexible woodlot management plans.

Resources

Canadian

- Bardekjian, A. (2004). A tree inventory management plan for the Toronto District School Board: FOR3008H Research Paper in Forest Conservation.

- BCIT Forestry. (2000). LSCR Big Tree Inventory.

- City of Charlottetown. (2015). Street and Park Tree Inventory.

- City of Edmonton. (2023). Natural Stand Valuation Guidelines.

- City of Toronto. (2013). Tree inventory practices and engaging volunteers on neighbourhood tree inventories.

- Green Municipal Fund. (n.d.). Factsheet: Urban forestry technology and tools – Which tools are right for your local context?

- Neighbourwoods. (2018). Neighbourwoods Tree Inventory and Monitoring.

- Puric-Mladenovic, D. (2016). Vegetation Sampling Protocol (VSP). Forests and Settled Urban Landscapes.

- Sherman, K. (2015). Creating an Invasive Plant Management Strategy: A Framework for Ontario Municipalities. Ontario Invasive Plant Council. Peterborough, ON.

Non-Canadian

- Charles T. Scott, C. T. & Gove, J. H. (2002). Forest inventory, Volume 2, pp 814–820 from Encyclopedia of Environmetrics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester.

- International Society of Arboriculture. (n.d.). Managing Hazards and Risks. Retrieved from TreesAreGood

- Morgenroth, J. and Östberg, J. (2017). Measuring and monitoring urban trees and urban forests. Routledge Handbook of Urban Forestry, 1, 33-48. ISBN 9781315627106

- PlanIT Geo. (2021). Tips for Planning an Urban Tree Inventory and Getting the Most Out of It.

- Pokorny, J., O’Brien, J., Hauer, R., Johnson, G., Albers, J., Bedker, P., and Mielke, M. (2003). Urban Tree Risk Management: A Community Guide to Program Design and Implementation. USDA Forest Service Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, St. Paul.

Tools and Inventory Protocols

- Canadian Institute of Forestry. (2024). Open Urban Forests – Establishing the First National View of Urban Forestry Geospatial Data in Canada.

- Eastern Ontario Model Forest. (1997). A True Picture: Taking Inventory of Your Woodlot.

- Green Municipal Fund. (2024). Factsheet: Urban forestry technology and tools.

- Forests Settled Urban Landscapes. (2016). Vegetation Sampling Protocol (VSP).

- i-Tree International Database. (n.d.). i-Tree International Database – About.

- Making Nature’s City. (n.d.). A science-based framework for building urban biodiversity: Overview.

- Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (Forest Analysis and Inventory Branch). (2018). Vegetation Resources Inventory – British Columbia Ground Sampling Procedures.

- Province of British Columbia. (2024). Ground sample inventories.

- Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). (2016). Forest Vegetation Monitoring Protocol – Terrestrial Long-term Fixed Plot Monitoring Program (Regional Watershed Monitoring and Reporting).

Further Reading

- Day, A. D. and Puric-Mladenovic, D. (2012). Forest inventory and monitoring information to support diverse management needs in the Lake Simcoe watershed. The Forestry Chronicle, 88(02): 140-146.

- Eisenman, T. S., Roman, L. A., Östberg, J., Campbell, L. K., & Svendsen, E. (2024). Beyond the Golden Shovel: recommendations for a successful urban tree planting initiative. Journal of the American Planning Association, 1-11.

- Esri Canada, City of Guelph. (n.d.). City of Guelph Imagery Viewer. Guelph GIS Maps.

- European Forum on Urban Forestry. (2018). Abstracts – Increasing cities, decreasing green areas – challenge to urban green professionals.

- Gougeon, F. A. (1995). A Crown-Following Approach to the Automatic Delineation of Individual Tree Crowns in High Spatial Resolution Aerial Images. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing, 21(3), 274–284.

- Haq, S.M., Waheed, M., Khoja, A.A., Amjad, M.S., Bussmann, R.W., Ali, K. et al. (2023). Measuring forest health at stand level: A multi-indicator evaluation for use in adaptive management and policy. Ecological Indicators, 150 110225.

- Improvement Service UK. (2016). Place-based Approaches to Joint Planning, Resourcing and Delivery: An overview of current practice in Scotland.

- Kudryavtsev, A., Stedman, R. C., & Krasny, M. E. (2012). Sense of place in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 18(2), 229-250.

- Ma, B., Hauer, R. J., Östberg, J., Koeser, A. K., Wei, H. and Xu, C. (2021). A global basis of urban tree inventories: What comes first the inventory or the program. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 60, 127087.

- Morales-Gallegos, L.M., Martínez-Trinidad, T., Hernández-de la Rosa, P., Gómez-Guerrero, A., Alvarado-Rosales, D., Saavedra-Romero, L.d.L. (2023). Tree Health Condition in Urban Green Areas Assessed through Crown Indicators and Vegetation Indices. Forests14, 1673.

- Nielsen, A., Ostberg, J., & Delshammar, T. (2014). Review of Urban Tree Inventory Methods Used to Collect Data at Single-Tree Level. Arboriculture and Urban Forestry 40, 96-111.

- Przewoźna, P., Mączka, K., Mielewczyk, M. et al. (2022). Ranking ecosystem services delivered by trees in urban and rural areas. Ambio51, 2043–2057.

- Puric-Mladenovic, D. and Baird, K. (2017). Natural areas monitoring in the City of Guelph: Emerald Ash Borer impact on ash populations in natural areas. Faculty of Forestry, University of Toronto. 76 pp.

- Rouge National Urban Park. (2024). Park management plan – Rouge National Urban Park. Parks Canada.

- Tuhkanen, E.-M., Männistö, A., Terho, M., Raisio, J., Arrakoski, K., Mänttäri, M., Riikonen, A., Tanhuanpää, T., Linden, L., & Verkasalo, E. (2018). Using city tree inventory data as a tool of planning, management and economic valuation of ecosystem services provided by urban trees. Abstracts: European forum on urban forestry 2018.

- Urban Forests Analytics. (2024). Tree inventories.

- Wang, L., Gong, P., and Biging, G. S. (2004). Individual Tree-Crown Delineation and Treetop Detection in High-Spatial-Resolution Aerial Imagery. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, 3(7), 351-357.

- Wood, C.M., Norton, L.R., & Rowland, C.S. (2013). What are the costs and benefits of using aerial photography to survey habitats in 1km squares? Natural Environmental Resource Council – Open Research Archive.