Highlights

Equity perspectives

Equitable urban forestry from social and ecological perspectives.

Environmental justice

Inclusive decision-making, equitable funding, community engagement, and education.

Multicultural considerations

People of different cultures and urban forestry.

Labour equity

Gender inequality in the fields of urban forestry, forestry, and arboriculture.

Where to start

Solutions and strategies for funding, planning, and engagement.

Importance of Equity in Urban Forestry

Urban forest equity is crucial to addressing the systemic and historical disparities of greening while supporting future environmental resilience. From a social perspective, urban forest equity is crucial to ensuring that marginalized and underserved communities receive fair investments in green spaces, that all communities have access to the health benefits of trees and greening, and experience equal opportunity to foster strong social connections, recreate, and thrive within urban green spaces. From an ecological perspective, urban forest equity is important for supporting biodiversity and overall ecosystem functioning, which improves climate resilience, provides wildlife habitat, and mitigates pollution.

Trends

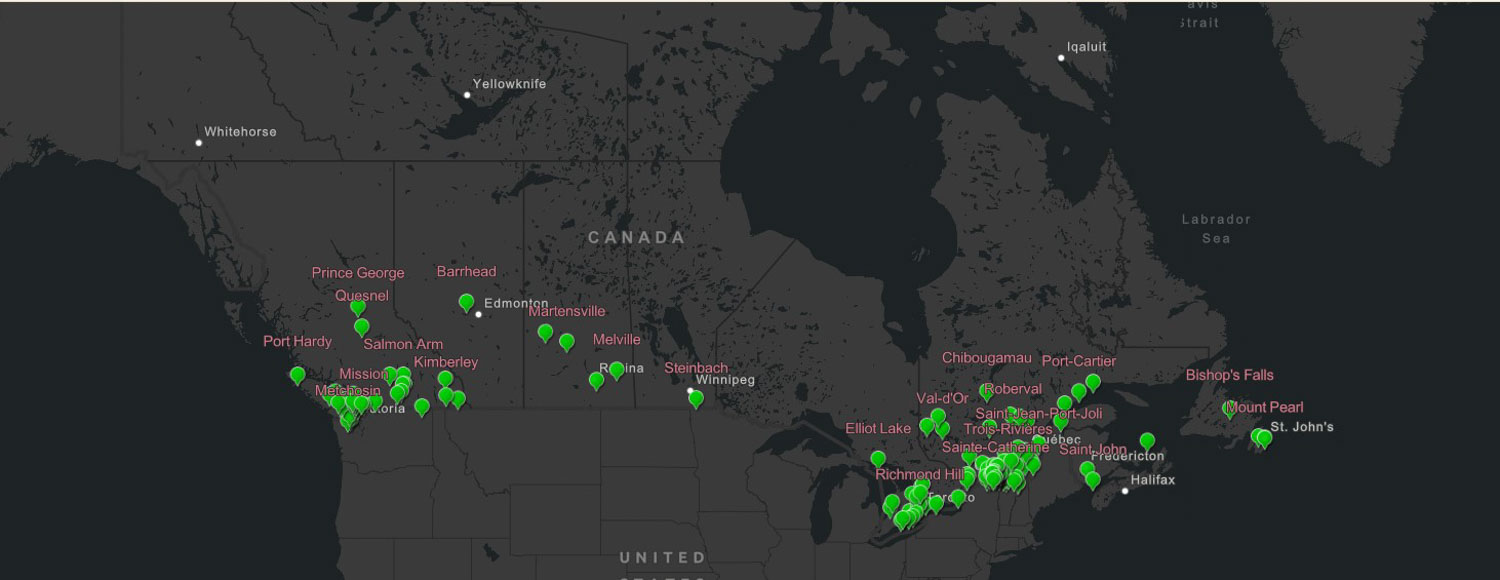

The importance of tree equity issues in Canada is gaining attention locally and nationally (Watkins & Gerrish, 2018). Urban forestry conferences, action plans, management strategies, and research are more intentionally integrating equity into their work across sectors in all regions. Some key research hubs contributing to knowledge advancements are: The University of British Columbia, The University of Toronto, Carleton University, Concordia University, UQAM, and Université Laval – to name a few. Researchers at these universities focus on social, environmental, or technological (such as AI) equity considerations.

Key knowledge includes:

- Access to tree canopy: There has been a significant shift in Canada, with more attention being paid to planting projects in underserved areas through the 2 Billion Trees program.

- Integrating a lens of environmental justice, for example, considering how temperature regulation can mitigate health risks due to extreme heat, particularly in low-canopy, health-vulnerable communities.

- Inclusive decision-making involving residents and ensuring their voices shape design, priorities, and practices.

- Equitable funding for tree planting and long-term maintenance to ensure disadvantaged areas are not overburdened with tree care post-planting.

- Community engagement to provide education, jobs, and training opportunities to foster long-term stewardship: A critical part of this is recognizing the role of Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous-led greening in community engagement to achieve equitable green spaces in planning and operations; in addition, increasing diverse group representation in urban forestry career pathways to support recognitional justice – they need to see themselves in the profiling of the field to feel welcome (Vabi & Konijnendijk, 2021)

- Lastly, there is emerging interest in credentials for urban forest professionals to support the "legitimization" of their role and skillsets (O'Herrin et al., 2023).

Defining Equity in Urban Forestry

The common definitions of urban forest equity in Canada center on the fair distribution of tree-related benefits, particularly in marginalized or underserved areas. Urban forest equity strives to ensure that all residents, regardless of income, race, or location, have equal access to the environmental, social, and economic benefits that urban trees provide.

Emerging research has shown that equity in urban forests goes beyond access to green space and should be broader to address three areas: distributional, recognitional, and procedural equity and/or justice (Nesbitt et al., 2019). These are not mutually exclusive. Distributional equity refers to the fair spread of urban forest resources and benefits across communities. Recognitional equity acknowledges and respects diverse identities, histories, and perspectives within communities. It is about understanding who lives in a community: where they come from, their unique needs, and the barriers they face in accessing green spaces. Lastly, procedural equity focuses on the fairness of decision-making processes, ensuring that all community members have a voice in urban forestry projects and that their voices influence outcomes.

Urban Tree Canopy Distribution and Access to Green Space

Urban forests are the first and only experience of nature for many, and these forests shape the experiences of nature for millions of Canadian residents, making access to urban green spaces a crucial topic in urban forest strategies; a national poll indicates that 95% of Canadians agree that access to green spaces is important to their quality of life (Environics Research, 2017). However, not all urban residents benefit equitably from the ecological services that urban forests and green spaces provide.

To date, urban forests have been distributed inequitably in Canadian cities. On average, lower-income neighbourhoods (below 50% of median household incomes) and marginalized neighbourhoods (disempowered or lacking the capacity to participate and gain full respect in society) have less green space and canopy cover than wealthier, predominantly white neighbourhoods (GoC 2022; Public Health Ontario, 2021; Cusick, 2021). In many Canadian cities, neighbourhoods with lower-income households and larger Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) populations were found to have up to 20-30% less canopy cover (Wittingham et al. 2022). When considering the physical and environmental health benefits that urban forests provide, the disparities in tree canopy distribution and inequitable access to these benefits raise a question of social equity (Schell et al., 2020). Moreover, in areas suffering from poverty and racialization, women have been found to use green spaces less frequently if they perceive them to be 'unsafe' due to poor lighting, maintenance, or cleanliness (Braçe, Garrido-Cumbrera & Correa-Fernández, 2021).

These findings show that low-income neighbourhoods, marginalized communities, racialized groups, and women do not equitably enjoy the benefits provided by quality green spaces. Addressing these issues and the equitable distribution of tree canopy and environmental benefits is essential for building just and sustainable treed urban communities and a healthy society. Community well-being, social inclusion, gender equity, environmental health, and climate resilience in racialized and low-income neighbourhoods will all benefit from equitable and strategic urban forest planning (Bikomeye et al., 2021).

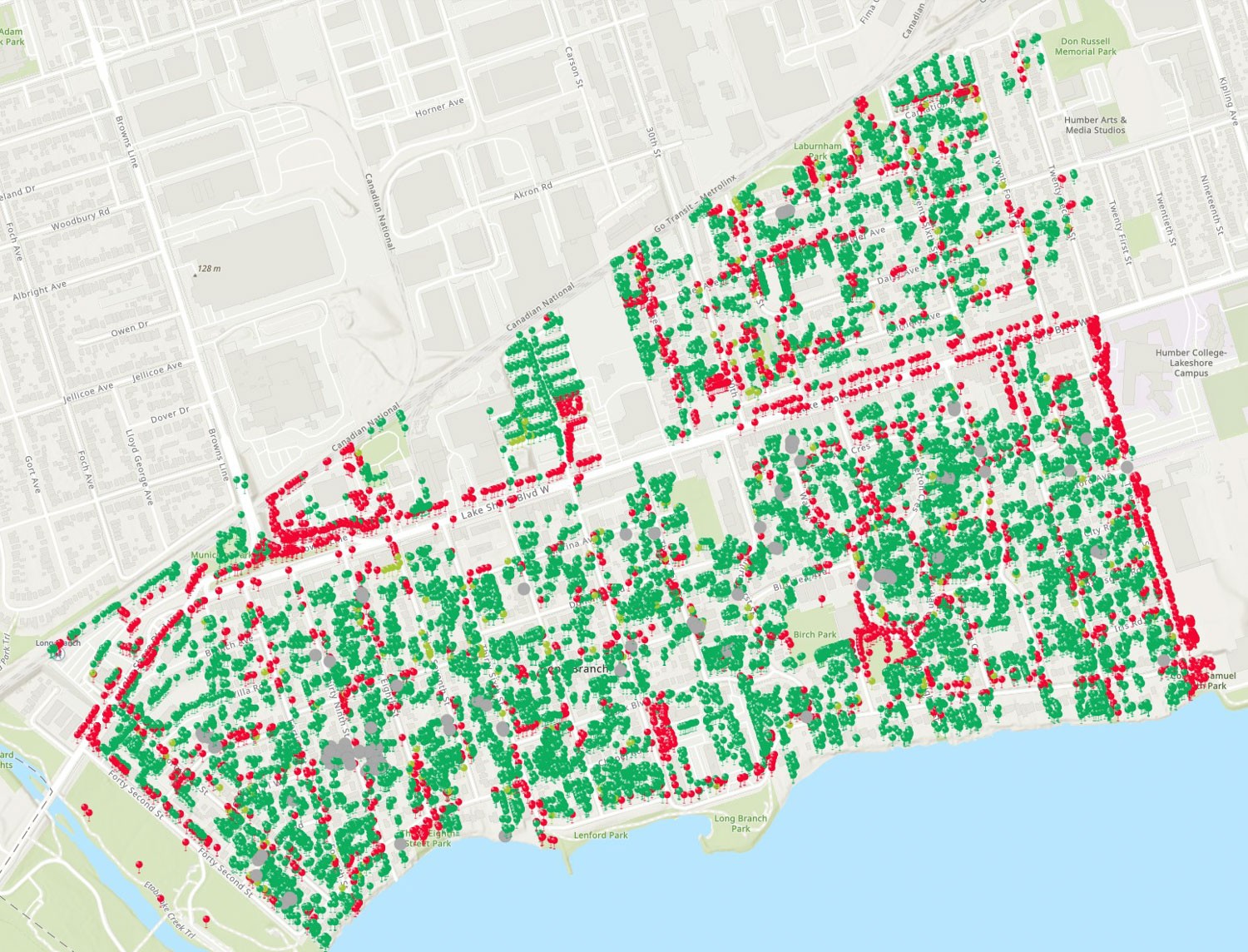

Canada is not immune to the issues of urban forest equity in its cities and towns. For example, in major cities such as Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary, Surrey, and Quebec City, the lower tree canopy cover has a significant negative correlation with poverty and racialization (Wittingham et al. 2022). In an effort to address the problem, municipalities like the cities of Ottawa and Toronto have made equitable access to urban forests a guiding principle in their urban forest plans and strategies (Engage Ottawa, 2024). However, despite the efforts, urban forest planning (meaning their development and planning) and tree canopy equality implementation in Canadian cities are still lacking, and equity strategies or engagement plans to assist specific to marginalized communities still have a minor impact (Mullenix, 2022).

Immigration and Multicultural Considerations

How Canadian citizens feel about their urban forest matters in terms of what they receive and benefit from, and whether and how they are willing to engage in urban forest conservation and management. Researchers often measure residents' attitudes toward green spaces through public surveys, and the information obtained can help municipalities better manage their urban forests (Jennings et al., 2016). However, people living in different regions may have different attitudes and preferences related to urban forests or may face unique barriers to their ability to participate in public referendums, surveys, and engagement opportunities (Avolio et al., 2015). Language barriers to new immigrants and people of various cultures can go unconsidered when municipalities conduct public surveys or hold open public participatory meetings (Ornelas Van Horne et al., 2023).

Additionally, low-income communities may lack time, funds, and access to the technology required to participate in events- time off work, childcare, internet, and computers/smartphones are more accessible in higher-income communities, but to many low-income Canadians, these things are luxuries that prevent participation (Chianelli, 2019). Meaningful public discourse cannot be achieved without considering barriers to engagement when discussing urban planning and environmental issues, especially in marginalized communities where sustainable and equitable planning is that much more significant.

Moreover, participation and inclusion of new Canadians, BIPOC, and multicultural individuals are also vital to building equitable urban forestry. Due to its far-reaching benefits, urban forestry involves multidisciplinary teams with diverse skills and knowledge. Foresters, urban planners, landscape architects, arborists, scientists, and community leaders help create healthy and sustainable urban forests, and this multidisciplinary field can greatly benefit from the inclusion of people from diverse backgrounds and experiences.

Labour and Gender Equity

Labour and gender equity are also crucial issues in the fields of urban forestry and arboriculture in Canada, where both sectors have traditionally been male-dominated. Labour equity focuses on ensuring fair representation, remuneration, and career advancement opportunities for individuals from all backgrounds. This issue is particularly important as the urban forestry profession seeks to diversify its workforce and attract more varied talent. Gender equity, on the other hand, specifically addresses the persistent underrepresentation of women in urban forestry and arboriculture, where women often occupy lower-level roles and encounter obstacles to career advancement due to systemic biases and discrimination (Bardekjian et al., 2019; Kuhns et al., 2004).

Recent efforts, such as mentorship/training programs and workshops aimed at reducing barriers to entry, are working to create more inclusive environments for women and other underrepresented groups in the field of urban forestry (City of Toronto, 2023; FSC, 2022). The biennial Canadian Urban Forest Conference, coordinated by Tree Canada in partnership with a host city, along with initiatives like Free to Grow, Women in Forestry, and Women in Wood networks, are helping to bring professionals together and advocate for a more equitable, diverse, and inclusive workforce (Free to Grow in Forestry, 2021; Women in Forestry, n.d.; Women in Wood, 2017). These initiatives are critical as urban forests play an increasingly vital role in the climate resilience and social well-being of Canadian cities, necessitating a broader range of voices and perspectives for their sustainable management.

As the field of urban forestry continues to evolve, addressing labour and gender equity within the profession will be essential for ensuring that all professionals, regardless of gender or background, can contribute meaningfully to the design, planning, and management of urban forests (Bardekjian, 2016; Bardekjian et al., 2019).

Solutions and Strategies

An equity-based approach to urban greening should be adopted to ensure that Canadian cities can work towards canopy cover goals without propagating further social and economic disparity (Angelo, MacFarlane, Sirigotis & Millard-Ball, 2022; Bassett, 2024; Puric-Mladenovic, 2024). Increasing canopy cover/tree planting goals are part of many Canadian cities' urban forest management plans, and urban greening in low-income/racialized areas presents an opportunity to address two issues at once. However, increasing canopy cover in underserved areas faces some challenges, such as a lack of funding, the absence of a planning process that values trees and long-term tree survival, and weak public engagement with communities that need trees the most (Mullinex 2022). Additionally, a lack of physical space to plant trees and sometimes environmental contaminants can lower chances of tree survival (Danford et al., 2014; Wattenhofer and Johnson, 2021).

Where to Start

There are several tools and methods that already exist for addressing inequality in urban forestry. For example, Statistics Canada created a tool to address the need to understand gentrification in a Canadian context. The tool is called GENUINE, which stands for Gentrification, Urban Interventions, and Equity (see Team INTERACT, 2016), and it automatically populates maps for several Canadian cities across four separate measures (Firth et al., 2021). In addition to assessing what is already there through available tools, there are recognition and certification programs such as the Arbor Day Foundation's Tree Cities of the World (TCOW) program and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative's (SFI) Urban and Community Forestry standards that offer structured guidelines and criteria for successful management. The first step is identifying a community’s equity-related goals; once goals are established, these kinds of tools can be helpful, staged approaches for planning and review.

Funding

To address the lack of funding for urban forestry activities, some municipalities, including Toronto and Winnipeg, support urban forestry grants and incentive programs (City of Toronto, 2021). Integrating urban forestry funding into yearly municipal budget planning is another way to ensure funding allocation to urban forest management. Alternatively, federal funding programs such as the 2 Billion Trees Program (GoC, 2023) and the Forest Innovation Program (NRCan, 2023) should work to enhance equitable access to urban forests and sustainable management of urban green spaces, while the Natural Infrastructure Fund (GoC, 2024) should improve natural infrastructure in underserved communities, which can reduce heat stress, limit extreme weather damage, and support stormwater management (Wittingham et al., 2021). Additionally, the federal government should increase funding availability for municipalities to protect and maintain existing trees and expand urban tree canopy equitably and fairly. One success story is the Growing Canada's Community Canopies (GCCC) program delivered in partnership between Tree Canada and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM), where there are two broad streams of funding: the first is for increasing canopy and getting trees planted, the second is for capacity building in all other areas that are required for urban forest sustainability.

Planning

Planning processes need to prioritize equity by using evidence-based decision-making informed by tools such as current tree inventories and the Tree Equity Index, income data, and immigration and BIPOC data (Ordonez et al., 2024). Additionally, municipalities must assess current canopy cover data compared to canopy goals while supplementing urban greening decisions by identifying areas with lower canopy cover, which have low Tree Equity Index values (Fleming and Steenberg, 2023). Integrated and intersectional planning processes for urban trees should be created, with adequate municipal and provincial funding allocation towards increasing urban tree cover equity across municipalities in racialized and marginalized communities (Jennings et al., 2019). Furthermore, these planned urban forests/green spaces must be accessible (within 300m of residences) and be of good enough quality to sufficiently supply benefits to underserved communities (Wittingham et al. 2022).

Engagement

Finally, fostering public engagement by building stakeholder relationships between governments, academia, industry, community organizations, practitioners, and citizens is vital to sustainable and equitable urban forest management (Campbell, Svendsen, Johnson & Plitt, 2022). Community members should be engaged from the beginning stages of planning processes and consulted throughout the planning and execution process. Nurturing ongoing relationships with existing neighbourhood associations and stewardship programs (or creating them where they do not exist) is an important step in starting discourse with residents. Consulting community leaders on equitable and accessible suggestions for building community interest and participation should be part of the beginning stages of public engagement strategies. Outreach efforts should be the predominant recipients of allotted urban greening budgets for target neighbourhoods in the beginning stages to ensure consideration of diverse perspectives, proper community consultation, and meaningful community engagement. Relationship-building with the people impacted by urban forest inequity can help make sure community needs are considered and responded to while building programs that are sustainable, successful, and robust (Wittingham, 2022).

Resources

Sources

- American Forests. (2021). American Forests launches nationwide tree equity scores.

- Angelo, H., MacFarlane, K., Sirigotis, J., & Millard-Ball, A. (2022). Missing the Housing for the Trees: Equity in Urban Climate Planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 44(3), 1415-1430.

- Avolio, M. L., Pataki, D. E., Pincetl, S., Gillespie, T. W., Jenerette, G. D., & McCarthy, H. R. (2015). Understanding preferences for tree attributes: the relative effects of socio-economic and local environmental factors. Urban Ecosystems, 18(1), 73-86.

- Bardekjian, A., Nesbitt, L., Konijnendijk, C., & Lötter, B. (2019). Women in urban forestry and arboriculture: Experiences, barriers and strategies for leadership. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, (46).

- Bardekjian, A. (2016). How perspectives of field arborists and tree climbers are useful for understanding and managing urban forests. The Nature of Cities; March 24, 2016.

- Bardekjian, A. (2016). Towards social arboriculture: Arborists' perspectives on urban forest labour in Southern Ontario, Canada. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 19, 255-262.

- Bassett, C. G. (2024). Bridging Gaps in Urban Forest Management to Achieve Urban Sustainability Goals. Thesis submitted to University of British Columbia.

- Bikomeye, J. C., Namin, S., Anyanwu, C., Rublee, C. S., Ferschinger, J., Leinbach, K., . . . Beyer, K. M. M. (2021). Resilience and Equity in a Time of Crises: Investing in Public Urban Greenspace Is Now More Essential Than Ever in the US and Beyond. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8420.

- Braçe, O., Garrido-Cumbrera, M. & Correa-Fernández, J. (2021). Gender differences in the perceptions of green spaces characteristics. Social Science Quarterly, 102(6), 9.

- Campbell, L. K., Svendsen, E. S., Johnson, M. L. and Plitt, S. (2022). Not by trees alone: Centering community in urban forestry. Landscape and Urban Planning, 224, 104445.

- Center for Social Intelligence. (2018). Addressing Systemic Gender, Diversity & Inclusion Issues in The Forest Sector.

- Chianelli, N. (2019). Examining the Barriers to Community Engagement in a Low-Income Lafayette Community. Purdue Journal of Service-Learning and International Engagement, 6(1), 36-44.

- Chow, R. (2024). Equity in urban forestry: Navigating the green challenges in cities. Tree Canada.

- City of Ottawa. (2024). Engage Ottawa 2024: Tree Planting Strategy.

- City of Toronto. (2021). Actions to Reaffirm Toronto's Tree Canopy Target – Report for Action to Infrastructure and Environment Committee.

- City of Toronto. (2023). City of Toronto opens applications for 2024 Women4ClimateTO Mentorship Program.

- Cummer, K., & Shandas, V. (2023). The equity of urban forest change and frequency in Toronto, ON. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 75, 127, 689.

- Curtis, J. (2024). Rooting for Tree Equity - Growing a Greener, Fairer Toronto. LEAF.

- Cusick, D. (2021). Trees are missing in low-income neighborhoods. Scientific American.

- Danford, R. S., Cheng, C., Strohbach, M. W., Ryan, R., Nicolson, C., & Warren, P. S. (2014). What Does It Take to Achieve Equitable Urban Tree Canopy Distribution? A Boston Case Study. Cities and the Environment, 7(1).

- David Suzuki Foundation. (2022). Greening Ottawa to Increase Resilience and Equity: Study on Citizens' Preferences Regarding the Urban Forest.

- Environics Research. (2017). TD GreenSights survey on how Canadians are using community green spaces. In: TD GreenSights Report - Creating a lasting legacy of community green spaces across Canada [online].

- Ferrell, C. (2023). Language justice in urban green initiatives. Environmental Health News.

- Firth, C. L., Thierry, B., Fuller, D., Winters, M., & Kestens, Y. (2021). Gentrification, Urban Interventions and Equity (GENUINE): A map-based gentrification tool for Canadian metropolitan areas. Health Reports, 32(5), 15–28.

- Fleming, A. and Steenberg, J. (2023). The equity of urban forest change and frequency in Toronto, ON. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 90, 128153.

- Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). (2022). FSC Strategic Framework on Diversity and Gender.

- Free to Grow in Forestry. (2021). Taking Action on Gender Equity in Canada's Forest Sector: Final Report 2021.

- Free to Grow in Forestry. (n.d.). Free to Grow in Forestry – Resources.

- Government of Canada (GoC). (2022). Towards a Poverty Reduction Strategy – A backgrounder on poverty in Canada.

- Government of Canada (GoC). (2023). 2 Billion Trees Program.

- Government of Canada (GoC). (2024). Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada – Natural Infrastructure Fund.

- Green Municipal Fund. (n.d.). Factsheet: Advancing tree equity and growing community canopies.

- HealthyPlan. (n.d.). HealthyPlan City – Explore Equity in Your City.

- Hsu, A., Sheriff, G., Chakraborty, T., & Manya, D. (2021). The tree cover and temperature disparity in US urbanized areas: Quantifying the association with income across 5,723 communities. PLoS One, 16(4), e0249715.

- Jennings, T. E., Jean-Philippe, S. R., Willcox, A., Zobel, J. M., Poudyal, N. C., & Simpson, T. (2016). The influence of attitudes and perception of tree benefits on park management priorities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 153, 122-128.

- Jennings, V., Browning, M. H. E. M., & Rigolon, A. (2019). Planning Urban Green Spaces in Their Communities: Intersectional Approaches for Health Equity and Sustainability (pp. 71–99). Springer.

- Kuhns, M., Blahna, D., & Bragg, H. (2004). Attitudes and Experiences of Women and Minorities in the Urban Forestry/Arboriculture Profession. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 30(1), 11–18.

- Martin, A. J. and Olson, L. G. (2024). A review of diversity, equity, and inclusion themes in arboriculture organizations' codes of ethics. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 50(2) 185-199.

- McDonald, R. I., Biswas, T., Sachar, C., Housman, I., Boucher, T. M., Balk, D., Nowak, D., Spotswood, E., Stanley, C. K., & Leyk, S. (2021). The tree cover and temperature disparity in US urbanized areas: Quantifying the association with income across 5,723 communities. PloS One, 16(4), e0249715.

- Mullinex, J. (2022). New Nature Canada Report Addresses Inequality in Cities' Tree Cover. Nature Canada.

- Natural Resources Canada (NRCan). (2023). Forest Innovation Program.

- Nature Canada. (2022). New Nature Canada report addresses inequality in cities' tree cover.

- Nature Canada. (2022). Canada's Urban Forests: Bringing the canopy to all. Nature Canada.

- Nesbitt, L., Meitner, M. J., Girling, C., & Sheppard, S. R. J. (2019). Urban green equity on the ground: Practice-based models of urban green equity in three multicultural cities. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 44, 126433.

- Nowak, D. J. and Van den Bosch, M. (2019). Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in and around urban areas. SANTE PUBLIQUE 31(1), 153-161.

- Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., Doyle, M., McGovern, M., & Pasher, J. (2018). Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in and around urban areas. Environmental Pollution, 232, 495–503.

- O'Herrin, K., Bassett, C., Ries, P., Wiseman, P. E., & Day, S. (2023). Borrowed Credentials and Surrogate Professional Societies: A Critical Analysis of the Urban Forestry Profession. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 49(3), 107–136.

- Ordóñez Barona, C., Jain, A., Heppner, M., St Denis, A., Boyer, D., Lane, J., . . . Conway, T. (2024). Gaps in the implementation of urban forest management plans across Canadian cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 251, 105168.

- Parish, J. (2020). Re-wilding Parkdale? Environmental gentrification, settler colonialism, and the reconfiguration of nature in 21st century Toronto. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 3(1), 263-286.

- Public Health Ontario. (2021). Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg).

- Puric-Mladenovic, D. (2024). Supporting Canada's Urban Forests Through Mapping and Fostering Community Stewardship – eLecture. CIF IFC.

- Salmond, J. A., Williams, D. E., Laing, G., Kingham, S., Henshaw, G. S., Dirks, K. N., ... & Maher, B. A. (2020). Urban trees and human health: A scoping review. Environmental Pollution, 263, 114, 201.

- Schell, C. J., Dyson, K., Fuentes, T. L., Des Roches, S., Harris, N. C., Miller, D. S., Woelfle-Erskine, C. A., & Lambert, M. R. (2020). The ecological and evolutionary consequences of systemic racism in urban environments. Science,369(6510), eaay4497.

- Scott, J. L., & Tenneti, A. (2024). Race in nature stewardship: an autoethnography of two racialised volunteers in urban ecology. Environmental Research: Ecology, 3(3), 035006.

- Team INTERACT. (2016). GENUINE: Gentrification, Urban Interventions, and Equity – Interactive maps.

- Vabi, V. & Konijnendijk, C. (2021). The Urgency and Opportunity to Increase the Access of All Canadians to Urban Forests: An interview with Dr. Cecil Konijnendijk on the 3-30-300 rule for creating greener and healthier cities to mark National Tree Day on September 22. Nature Canada.

- Vogt, J., Hauer, R. J., & Fischer, B. C. (2015). Urban forestry and arboriculture as interdisciplinary environmental science: importance and incorporation of other disciplines. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 6(2), 371–386.

- Watkins, S. L., & Gerrish, E. (2018). The relationship between urban forests and race: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Management, 209, 152–168.

- Wattenhofer, D.J. and Johnson, G.R. (2021). Understanding why young urban trees die can improve future success. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 64,127247.

- Whittingham, E., Vabi, V., Lalloo, S., and Hak, S. (2022). Canada's Urban Forests: Bringing the canopy to all. Nature Canada.

- Wolf, K. L., Lam S. T., McKeen, J. K., Richardson, G. R. A., van den Bosch, M., and Bardekjian A. C. (2020). Urban Trees and Human Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12):4371.

- Women in Forestry. (n.d.). Women in Forestry – About [webpage].

- Women in Wood. (2017). Women in Wood – About [webpage].

7.0 Social Considerations

7.1

Equity Considerations in Urban Forestry

7.2

Awareness and Community Stewardship

7.3

Indigenous Collaboration and Integration of ITK

7.4

Education and Professional Development